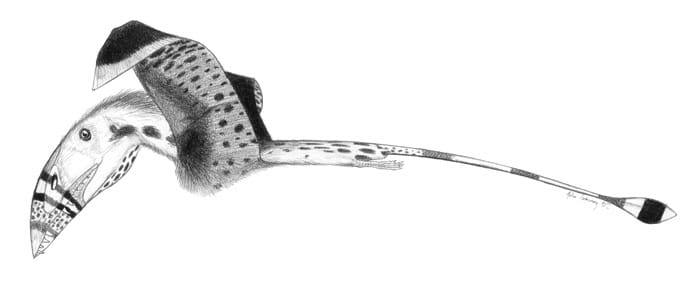

Life Restoration by Mark P. Witton (CC BY 4.0)

About 195 million years ago, long before the first birds appeared, a strange flying reptile lived along the coastal cliffs and forests of what is now southern England. This was Dimorphodon macronyx, one of the earliest pterosaurs known from well-preserved fossils. Its name means “two form tooth,” a reference to the very unusual mix of tooth shapes in its jaws. The teeth alone set it apart from many early flying reptiles, but the rest of its anatomy is just as remarkable.

Dimorphodon macronyx skull and partial skeleton (natural size), from the Lower Lias of Lyme Regis, British Museum. Photo: James Erxleben (Public Domain).

Dimorphodon was not the sleek, long-winged pterosaur many people imagine. Its head was large and deep with strong jaws and a blunt snout. When Richard Owen first described it in 1859, he noted that the skull contained air spaces similar to the skulls of modern birds. These cavities reduced weight while keeping the skull strong. The combination of a powerful head and varied teeth suggests an animal capable of handling different types of prey. The long pointed teeth at the front were well-suited for grabbing moving animals, while the shorter teeth behind them helped process whatever it caught.

Illustration by John Conway (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Adults reached a wingspan of about one meter, or roughly three feet, which is short for a pterosaur of its overall size. The wings were supported by an elongated fourth finger, but the rest of the limbs were unusually long and robust. The hind limbs were strong and the tail was stiffened by long supporting rods. These features have led many paleontologists to think Dimorphodon spent considerable time climbing. It likely used its claws to grip tree trunks or rocky surfaces, which would have helped it launch into flight from higher perches.

Fossils from Dorset and other parts of southern England show that early Jurassic coastlines offered a rich variety of food sources. Shorelines, tidal zones, and forested cliffs provided insects, small vertebrates, and possibly fish. Dimorphodon’s mixed teeth fit well with these environments. Some researchers propose that it hunted small animals on the ground or in vegetation and used flight mainly to move between perches. Others suggest it may have caught prey during short flights, but its short wings and strong limbs point toward quick bursts of flapping rather than long distance travel. It seems to have relied on agility in tight spaces instead of soaring over open water.

Mounted skeleton of Dimorphodon macronyx, Early Jurassic pterosaur (Petrified Forest National Park exhibit) Photo: Frank Kovalchek (CC BY 2.0)

The tail of Dimorphodon has also drawn attention. Some early pterosaurs carried a diamond-shaped vane at the tip, and some scientists think this structure helped with stability during flight. Others caution that the exact aerodynamic function is difficult to confirm because Dimorphodon’s soft tissues are not fully preserved. What is certain is that its stiffened tail would have added balance while climbing or shifting between branches, making the tail an important part of how this pterosaur controlled its movement.

Dimorphodon fossils help fill a gap in our understanding of early pterosaur evolution. Later pterosaurs often had long wings and highly specialized feeding strategies. Dimorphodon represents an earlier stage when pterosaurs were still experimenting with body shapes, teeth arrangements, and different ways of living. It shows that flight did not begin with refined aerodynamics. It began with animals that mixed climbing, short flights, gliding, and powerful jaws in combinations that worked for their environment.

Cast of Dimorphodon macronyx fossil from the Blue Lias Formation of Dorset, United Kingdom (~200 million years ago), on display in 'Pterosaurs: Flight in the Age of Dinosaurs' exhibit (NHM London specimen). Photo: Tim Evanson (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Although most Dimorphodon fossils come from England, related species have been identified in Mexico. These discoveries show that pterosaurs spread widely during the early Jurassic and adapted to coastal landscapes around the world. Each new find adds to the picture of how they diversified and how early flight evolved.

Dimorphodon was neither a dinosaur nor a bird. It belonged to a separate lineage of flying reptiles and played an important role in the long story of life taking to the air.

How did you feel about today’s issue?

Did You Know? The first Dimorphodon fossils were uncovered in the same region of England where English paleontologist Mary Anning made many of her groundbreaking discoveries. Although she did not name Dimorphodon herself, she found several of the fossils that later helped scientists understand early pterosaurs. Her work in Lyme Regis provided some of the key specimens that shaped the earliest research on prehistoric flight.

Till next time,